Whatever happened to…?

11/1/2023Des Moines is considered a small market, at least for media, entertainment and designers. That’s changing now in a world flash-shrunk by the Internet. Before the last 20 years, most Iowa artists with ambition left the state, usually for New York. Iowa was more famous for the people who left and made it there — Halston, Larry Zox, Andy Williams, Johnny Carson, Donna Reed, Glenn Miller, Bix Beiderbecke, Ashton Kutcher — than the people who stayed.

Now many artists can make it here because the world wide web is their marketplace. Mainframe Studios reserves 20% of its studios for out-of-state artists moving to Des Moines. When Moberg Gallery opened 20 years ago, they only handled local artists. Now they represent artists from all over the country and the world.

Iowa is more hospitable to ambitious people than ever. But it’s tempting sometimes to wonder whatever happened to people who were once household names here and then left the Iowa public eye. We looked for some answers.

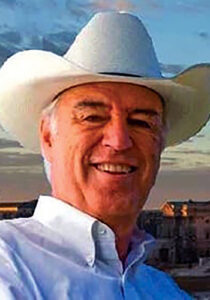

Chet Culver

Chet Culver

You can take the politician out of politics but you can’t take politics out of the politician.

Chet Culver, a former teacher at both Roosevelt and Hoover, was the 41st Iowa Governor, winning office over Jim Nussle by nearly 10 points in 2010 after a hotly contested primary. On paper, the former Secretary of State’s one term looked pretty good. He balanced the budget, raised the minimum wage for the first time in over a decade, lowered unemployment, and advocated hard for renewable energy while seeing Iowa rise to top three status in both wind and ethanol production. He had favorable ratings (60% approval) for his handling of the 2008 floods. He pushed legislation, and ended mandates, to make stem cell research easier, and to fund it.

He was also elected as federal liaison for the Democratic Governor’s Association. He appeared to be a rising star in a party buoyed by Barack Obama’s sweeping victory in 2008.

Despite putting himself out there to voters as a former football and basketball coach and current kite flyer, he just didn’t connect to the electorate. His reelection effort in 2014 was disastrous. As incumbent, he lost by 10 points to Terry Branstad. Obama’s coattails were long gone after two years when voters responded to the unpopular health care legislation that dominated Washington for two years. Branstad was helped by his running mate, Kim Reynolds, more than Patty Judge helped Culver. Culver’s wife, Mari, was not much of an asset. She got caught smoking in her state limo after the smoking ban her husband pushed had become law.

Culver was a gracious loser, praising his opponents and the electorate, whom he thanked for giving him his chance. He bid farewell and conceded the election on the stage of the Hotel Fort Des Moines, overseen by his father, John, who had conceded his U.S. Senate seat to Chuck Grassley on the same stage in 1980.

Chet Culver had grown up in the D.C. suburbs and gone to college at Virginia Tech on a football scholarship. He moved to Iowa, studied at Drake and became active in party politics. Some say he was perceived as a carpetbagger here.

After his loss, Culver created his own lobbying/consultancy company, Chet Culver Group, which specializes in renewable energy ideas and “cutting through the red tape.”

Jim Ross Lightfoot

Mari Culver is more locally prominent now than the ex-governor. In 2019, she was arrested for public intoxication on the midway of the Iowa State Fair. She pled guilty to a simple misdemeanor. In April, she was named Assistant County Attorney in Polk County under Kimberly Graham, a Democrat. She had been out of a job since Tom Miller lost Iowa’s Attorney Generalship to Brenna Bird in last year’s midterm elections. Mari Culver was one of 19 Miller employees who were “asked” to resign.

Chet took a job on the board of directors for the Federal Agriculture Mortgage Corporation where he serves today after a brief pause. Lobbyist and bureaucrat, our ex-governor obviously knows where the money is — and how to cut through the red tape to procure it for clients.

Jim Ross Lightfoot

Jim Ross Lightfoot was another rising political star in the 1980s and 1990s. On paper, he was a Conservative dream candidate. Born in Sioux City’s Florence Crittenton Home for Unwed Mothers, he grew up on a southwest Iowa farm and graduated from David Farragut High School. He moved from a high school named for a war hero to eight years in the U.S. Army and U.S. Army Reserve.

He began his business career with IBM as an engineer. The company moved him to Oklahoma where he also served with the Tulsa Police Department. He returned to southwest Iowa in the early 1960s and worked for KMA, a powerful 100,000-watt radio channel in Shenandoah. KMA broadcast farm news and hosted “school” shows and live music. Founded by gardening mogul Earl May, the station boasted that 100,000 people visited Shenandoah to see its shows, which launched the career of the Everly Brothers.

Lightfoot garnered a following at KMA and ran for Tom Harkin’s vacated seat for the U.S. Congress in 1984. His victory turned southwest Iowa red politically, giving Lightfoot statewide clout. In 1996, Lightfoot kept a 12-year-old promise to only run for six terms in Congress and then challenged Harkin for his U.S. Senate seat. Despite losing, the race made him a face of the Republican party.

In 1998, he ran for Governor against a relatively unknown state senator named Tom Vilsack. Lightfoot was considered the frontrunner for the entire campaign. The race fooled most pollsters, and Lightfoot lost in an upset. (Vilsack campaign guru Jerry Crawford had predicted the upset a week early.)

Most of the commentary about the upset hit on Lightfoot’s casual campaign that seemed to assume victory and took no chances with ideas or promises. His TV ads were ridiculed (including in CITYVIEW) for focusing on his being an orphan.

Greg Ganske

Before 1998 ended, Lightfoot followed his inner cop and joined Forensic Technology, Inc. as a vice president. Crime was no match for the revolving door of politics, though, and he became a non-attorney advisor for Washington D.C. power firm Buchannon, Ingersoll and Rooney. He was attached to the firm’s Federal Government Relations division.

In 2009, he started his own firm, Lightfoot Strategies. He lives with wife, Nancy, in White Oak, Texas, a town of 6,200 that is closer to Shreveport than Dallas and did not even exist when Lightfoot began announcing for KMA. He has four children and four grandkids.

Greg Ganske

Not all Iowa pols retire to the revolving door of lobbying. Greg Ganske went from plastic surgery to U.S. House star. He, too, made the mistake of running against Harkin for the Senate. He was beaten by double digits. Ganske then simply went back to his Des Moines surgery practice.

The baller, the welder and a story better than fiction

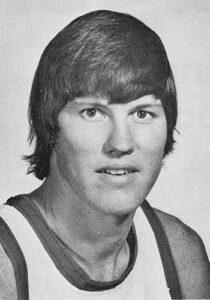

Dow Mossman and Bob Netolicky are intertwined in lore and totally separated by reality’s fickle fate. Neto became a basketball superstar, first at Drake and later with the Indiana Pacers. He was four times all pro and won two championships. Yet he never played high school basketball in Cedar Rapids. He tried out and was a first cut as a freshman.

Bob Netolicky

Dow Mossman wrote a brilliant novel that vanished after mediocre sales for much of his lifetime. The epic, “Stones of Summer,” was the great Iowan novel for boomers with lots of reading time. The book jacket compared Mossman to Faulkner and Joyce. Mossman spent nine years on the copy of the book and admitted that it was taken away from him lest he never submit it.

Mossman and Neto were best friends growing up in the nice part of Cedar Rapids in the 1950s and 1960s. In the book, Netolicky’s persona was called “Dunker” and his father, a Cedar Rapids surgeon, was called “Zipper.”

Neto was part of Maury John’s great era at Drake. He was as famous for eccentricities as for his cage skills. In Des Moines, he lived with ocelots and even a lioness (and also with John Lynch, the father of Hall of Fame footballer and 49’ers GM John Lynch, Jr.).

Neto became the most famous sports star in Indianapolis. His bar, Neto’s, was the hottest place in town for decades, drawing Indy race car drivers, NBA players, politicians, media stars and NFL stars. (It’s ashes now.) Neto continued to play larger than his 6’ 10” size. The Indianapolis Star labeled him “the Broadway Joe of basketball,” and the “man who makes women swoon.”

His late life mission has been to make former ABA players eligible for NBA player pensions. The most recent story about him, in 2022, interviewed him “from his home in Texas.”

Dow Mossman

After “Stones,” Mossman made a living as a welder and newspaper bundler in Cedar Rapids. Thirty five years after “Stones of Summer” went out of print, a young scholar and film maker, Mark Moscovitz, called Mossman. The filmmaker, famous mostly for creating political stars all over the world, had found a copy of “Stones” and loved it. He wrote a book about it, “The Stone Reader,” and made a film.

Moscovitz’s work inspired a reprinting of Mossman’s book. A second generation of readers now identify with his “coming of age” masterpiece. Both Mossman and Netolicky are now in their early 80s.

Staying around inconspicuously

Dr. Gregory Schmunk was Polk County’s most conspicuous medical examiner. He had come from San Francisco and Sacramento where he had been involved in some famous situations, from hostage events to consulting on TV shows like “CSI.”

In Des Moines, he was loved by attorneys for testifying as an expert witness. He also ruffled feathers and was fired in 2020. Schmunk didn’t go anywhere. He’s doing quite well as owner and chief pathologist for Urbandale Forensics Inc. He has performed more than 6,300 forensic examinations and testified in more than 500 criminal trials.

Dr. Gregory Schmunk

Where did the chef go?

Des Moines has become more of a magnet for great chefs than it used to be. Lots of guys came here because their wives got good jobs, many in publishing, or wanted to move home. Sean Wilson of Proof, David Baruthio of Baru 66, Alex Hall of St. Kilda’s, and Mark Navarre of Purveyor came from Carolina, France, Australia, and the Basque country, respectively.

Baru now has restaurants less than 10 miles apart on both sides of the France-Switzerland border. But what happened to the others who got away? Rob Beasley was a pioneer of the merging restaurant scene here three decades ago. He opened “ahead of their time” cafés in Adel and Des Moines, the best known being The Varsity.

He’s still in the business and has been in charge of the kitchen for Chaumette Vineyard and Winery south of St. Louis. In October, the owners put that place up for sale. It had been named one of “America’s 10 best wineries” by USA Today. Beasley posted his resume for now, new owners and their plans being unknown.

John Ross, like Beasley, was part of the beginning of the new DSM dining scene. His Sage, with Andrew Meek, was a signal moment in metro dining. Ross moved on to Chicago when Sage ended. He owned restaurants there that were considered top 10 by the Chicago Tribune. Last year, he was shot in the leg. He recovered and sold the business. He is married to Tryphena Wong Ross, whom he met in his restaurant. She is a grad of Des Moines University. The couple recently had their first child.

Rob Beasley

“Everything is better with some cows around.” — Corb Lund

In Texas, songs lament the disappearance of the cowboy from the American landscape. Paula Cole became a star with her song “Where Have All the Cowboys Gone?” while Willie Nelson advised “Mamas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys” (which was written by Ed and Patsy Bruce).

In Iowa, people older than 60 wonder where the cows went. Since World War II, Iowa has gone from the nation’s leader in cattle production to 10th. Everly High School used to proudly call their sports teams “Cattlefeeders” and “Cattlefeederettes.” Today they are the Mavericks, but the Everly Cattlefeeders Facebook page has 450 followers.

Sioux City’s reputation as a rowdy town was based on its slaughterhouse history. Farmers would bring their cattle to town and celebrate in manners unacceptable in rural Iowa.

When the cattle were there, northwest Iowa was the state’s best showcase for steakhouses. Towns with less than 200 people — Craig, Mineola, Wiota, Doon — had steakhouses that people drove 100 miles or more to enjoy. All but Craig still have steakhouses.

Theo’s in Lawton, Archie’s Waeside in Lemars, and Fireside Steakhouse in Anthon thrived because they were close to population areas in Sioux City and Lemars. Archie’s is a James Beard prize-winning legend with its own garden and aging room. They cure their own corned beef for the lazy Susan service.

But the legend of the genre was a soldier’s dream made reality. The Hawarden Steakhouse was built by WWI vet Seal Van Sickle, who cleared timber and dislodged limestone boulders from the Sioux River and carried them uphill. He painted a marvelous mural of “The Mermaid” in his Rendezvous Lounge. It was said to be of a lady he met in France.

But the legend of the genre was a soldier’s dream made reality. The Hawarden Steakhouse was built by WWI vet Seal Van Sickle, who cleared timber and dislodged limestone boulders from the Sioux River and carried them uphill. He painted a marvelous mural of “The Mermaid” in his Rendezvous Lounge. It was said to be of a lady he met in France.

The last time I visited, the original beams and boulders were still in place, though the wood fire oven had been converted to gas. The last time I tried to visit, I was threatened with violence by a paranoid owner who didn’t last long. The fate of the Hawarden is that of Iowa cattle lore — grandeur in the rubble.

Where did the cattle go? Like most American populations and culture since the world wars, it went west and south. Iowa was huge in cattle when family farms were the rule of the day. Farmers raised multiple crops and animals. When factory farms seized the state’s agriculture psyche, one and two crops ruled. It became too expensive to graze cows on the world’s most expensive farm land. The cows and the cow processors moved to cheaper land. Texas, California, Nebraska, Kansas and Oklahoma are now the top five cattle states.

Iowa steakhouse culture moved, like the population of the state, from farms and small towns to big cities and suburbs. More than half of Iowa’s 99 counties peaked in population by the turn of the century, the 19th century’s turn into the 20th.

Dolph Pulliam

Ending with a perfect circle

Another star in Maury John’s basketball story, Dolph Pulliam, was possibly as well-known as anybody in Des Moines. After leading Drake to the Final Four, Dolph worked in TV and radio, as both a children’s show host and sports announcer. He left TV for a full time job in community relations at Drake.

A little known story about Dolph’s life is that he was orphaned young, along with a large family of siblings, in Missouri. His parents paid with their lives for the sin of buying property while Black in the wrong part of the Show Me state. The kids were all taken in and raised by relatives in Gary, Indiana.

After many decades of service to Drake and Des Moines, Dolph moved back to Gary in retirement, to give back to the kin of the people who raised him. ♦