The trailblazers who built Des Moines

6/5/2024Des Moines was forged by God, chance and indefatigable human will. The city that would become Iowa’s capital was birthed by the divine coincidence of two life-supporting rivers harrowed by millennia of meanderings dictated by what poets call the unseen hand and believers call God.

The coincidence of those rivers meeting at a nearly perfect right angle decreed the future city’s place on Earth. It became the capital of the world’s greatest agricultural bounty by the fickle fate of human politics.

How it developed beyond that is a story of adventurers who engineered the ferry crossings, railroads, highways and magnificent constructions that defined Des Moines. This is a story of four 19th-century men who dared to build something out of nothing more than the mergence of two rivers.

1843

Present day Des Moines was inhabited many times between 1300 and 1700. Some 18 Native American burial mounds were discovered and leveled by early settlers. The city those pioneers built can refer its history to 1843 when James Allen led an army expedition to what he called Fort Raccoon. The U.S. War Department changed the name to Fort Des Moines. The intentions of Des Moines’ founding heroes would be similarly overturned or forgotten time and again by outsiders from other centuries.

The year 1843 was pivotal in America’s self-discovery. War hero William Henry Harrison had been elected, the last president born under British rule in 1840, but he died after 31 days in office. His Whig party successor John Tyler dropped out of the 1844 presidential election and endorsed James Polk, a Democrat and war hero running against Henry Clay. That was 40 years after Lewis and Clark reported the marvels of the Oregon Country, land hotly disputed between the U.S. and Britain. Tyler commissioned troops to build barracks “at the junction of the Raccoon and Demoines rivers.”

The first non-military construction there was built by traders, brothers George Washington and Washington George Ewing. Settlements followed quickly because the rivers were navigable then, all the way to the Mississippi.

While north and south battled over the soul of the nation, eastside and westside fought to host the new capital of Iowa. Candidates in the first gubernatorial election following statehood supported opposite banks of the Des Moines River. The territorial government designated a site in Jasper County. The succeeding governing body rescinded that in 1843. Another 14 years would pass before Fort Des Moines was redesignated Des Moines and named the state capital.

The zeitgeist of 1843 was “westward ho.” Wagon trains from Iowa to Oregon — which then included present-day Oregon, Washington and British Columbia — would settle the dispute between the U.S. and Britain in America’s favor, at the 49th parallel minus Vancouver Island’s southern part.

The capitol building was about bragging. Originally, it was commissioned by the state legislature with the stipulation that it: proceed immediately, cost no more than $1.5 million, and be constructed with money on hand and without raising any taxes or creating new ones. That was wishful thinking. The construction lasted 17 years. No architect stuck around for half the duration, and only one succeeding generation architect saw it through.

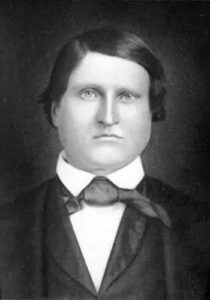

William Alexander Scott. Photo courtesy of Terrace Hill

The ferryman

The man who did more than anyone to will its construction was William Alexander Scott, one of the first white men to observe “the valleys of the ’Coon and Demoines.” He came as a dragoon in 1843 and stayed until he helped move the Sauk and Meskwaki to Kansas. They had become troublesome after white traders like the Ewings introduced them to booze. Scott returned from Kansas a few years later to found East Des Moines, purchasing 500 acres.

Scott flourished by monopolizing the flatboat ferry business, the only way more than a very few could cross the rivers until the first railroad bridge was built decades later. One historic account said Scott moved as many as 600 horses a day for wagon trains that would redefine the borders of the nation. Another mentioned that he was adept at taking advantage of drunken, anti-Prohibition legislators needing to cross the river after celebrating a win.

Scott ended the east-west feud over the capitol’s situation by giving Iowa the 10 acres around which it now stands. In the meantime, he built a three-story, temporary statehouse with his own money. It would serve as the de facto capitol for 30 years.

Scott’s modest grave is the only one on the capitol grounds, in a spot he had asked to be laid to rest.

The rail baron

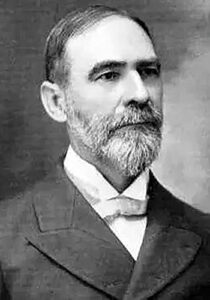

Benjamin Franklin Allen was born in Indiana in 1829 and orphaned at the age of 4. He lived with a grandfather until 17 and received no formal education. After serving two years in the army, he ventured to Fort Des Moines in 1848, probably to collect an inheritance from his uncle James Allen, the man who led the first military expedition there.

Benjamin Franklin Allen.

Photo courtesy of Terrace Hill

The younger Allen started a steam sawmill near town and opened a general store that advertised “silk dresses and goose yolks.” Sensing more money could be made in other things, he began careers in banking and real estate by acquiring 34 acres of land including the future site of Terrace Hill.

At one time, Allen’s land holdings in central Iowa were estimated to include 93 square miles. In 1857, he became a director of the State Bank of Iowa. He then acquired a controlling interest in the Bank of Nebraska, which he managed from Des Moines. During the Panic of 1857, Allen kept many local businesses afloat by endorsing promissory notes.

That made him a local hero. He was elected to Des Moines City Council in 1860 and represented Polk County in the state legislature from 1870-73. Senator Allen was influential in securing legislation to finance the new Capitol.

In 1865, Allen organized the Rock Island Railroad. By 1867, the railroad reached Des Moines, and Allen was appointed to hold in trust more than $500,000 in bonds of the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific Railroad. He bought property along its proposed route west to the Missouri River, established a land company, plotted town sites along the route, and sold them at a big profit.

Iowa’s first millionaire, Allen’s fortune was estimated as much as $12 million at its height. Unfortunately, he used the railroad trust funds to speculate, a decision that would contribute to his financial ruin.

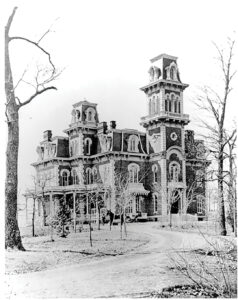

Allen married Arathusa West and built Terrace Hill north of the Racoon River on 29 acres between 17th and 29th streets. He selected Chicago architect William W. Boyington for a house that contained very modern features: hot and cold running water, gas lighting, an elevator and indoor bathrooms. Situated on the highest hill in Des Moines, the estate boasted pathways, fountains, an arbor, a greenhouse and formal gardens. The final cost was approximately $250,000.

Terrace Hill 1869. Photo courtesy of Terrace Hill

The Allens hosted an 1869 housewarming for 700 guests. They reportedly spent $8,000 on food, flowers and entertainment. The food included “two fruitcakes weighing twenty-five pounds each, ice cream molded in the figure of George Washington, a twenty-five-pound lady cake, oysters, boned turkeys in colored jellies, and a variety of meats.”

In May 1873, Allen’s debt became significant, having borrowed railroad trust funds for his own investments. To pay them off, he purchased controlling interest in the Cook County National Bank in Chicago and was elected president. That bank crashed in January 1875, taking Allen down with it.

Litigation liquidating Allen’s estate dragged on for a decade. One criminal trial for fraud went to the U.S. Supreme Court. Allen escaped conviction as juries believed he had good intentions. He managed to retain possession of Terrace Hill and eight acres of immediate grounds until 1884, when Frederick M. Hubbell purchased the property for just $60,000.

Allen’s simple gravestone is in Woodland Cemetery with his death date wrongly inscribed.

The swashbuckler

Francis Marion Drake was born somewhere in Illinois in 1830 and came to what became Appanoose County when he was 7. Before turning 20, he led two expeditions of Iowans to gold rush California. On one occasion, he beat off an attack of 300 Pawnees without major casualties. On his second trip, he introduced English cattle to California. Returning from that trip, he survived a shipwreck that killed 800 fellow passengers.

A general, he fought in several Civil War engagements for Grant’s Army of the West. He was severely wounded at the Battle of Mark’s Mills. Fourteen months later, he returned to service, with increased command assignments.

Francis Marion Drake courtesy of Drake University

A war hero, he returned to Centerville and practiced a few years as a criminal attorney. By then, railroads had crossed the Mississippi and changed Iowa forever. Drake’s keen nose for destiny, and accumulating wealth, drew him to the iron horses. He built three railroads and directed them to the coal mines of Appanoose County. He founded the Centerville National Bank.

In 1881, the Disciples of Christ Church decided to transfer its support for Oskaloosa College to a new college to be built in the woods outside Des Moines. They announced that the largest financial pledge to the project would include naming rights. Drake, a church member, easily outbid everyone with a $20,000 pledge in railroad bonds.

Drake built Old Main in less than two years ending in 1883, personally contributing two thirds of the cost. He incentivized rapid construction by offering $20 per thousand bricks laid. He learned that trick building railroads. Old Main remains the most striking construction on a campus that has attracted several of the 20th century’s greatest architects.

Though the city was still without paving or sewers, Drake University grew dramatically. In less than 10 years, it included eight departments, 53 professors and 800 students. Under Francis Drake’s order, it featured a School of Music that remains a claim to fame.

In 1895, he was elected Iowa Governor. During his tenure, the state enlisted the federal government to build its Beaux Arts “City Beautiful” project that would lead by 1920 to the Post Office building that is now part of Polk County Administration, the library that became the World Food Prize building, the Armory, City Hall and the Police Station.

A large obelisk marks Drake’s grave in Centerville, but Old Main is his memorial.

Old Main courtesy of Drake University. George Carpenter climbed an elm tree and said to Francis Marion Drake, “This is where we shall build our University.”

The ‘Chief’

Unlike the other trailblazers in this tale, Thomas Harris MacDonald was born not east but west of Iowa. His Scottish parents left Poweshiek County to prospect in Colorado. They returned to Iowa in time for him to begin school in Montezuma.

His father was partner in a seed and lumber dealership. At that time, lumber traveled in wooden wagons that were unusable in mud. As late as 1920, 90% of all U.S. roads were dirt, and most of the rest were gravel. Farm produce often rotted on its way to market. Thomas grew up frustrated with the limited functionality of Iowa roads.

He noted that it cost more to deliver seeds and lumber the last couple miles of a trip than the first thousand miles on the railroad. The term “the last mile” has been used in transportation economics ever since.

MacDonald went to Iowa State College of Agricultural and Mechanical Arts in Ames, receiving a degree in civil engineering in 1904. His senior thesis was “Iowa Good Roads Investigations.” After graduation, MacDonald was named Assistant in Charge of Good Roads Investigation for the Iowa State Highway Commission. He quickly became Chief Engineer and then Iowa Highway Commissioner.

He was then named president of the American Association of State Highway Officials and was suggested by that group to serve as U.S. Chief of the Bureau of Public Roads. Congress immediately appointed him to that new post during the Wilson administration.

Thomas MacDonald, courtesy of Iowa State University

MacDonald pulled together a coalition of 10 bureaucracies, chambers of commerce and trade associations. He became known as “Chief – the man who builds roads.” Road building meant job creation, and MacDonald’s celebrity became larger than life.

In its “Road Warriors” episode of “The Engineering That Built the World,” the History Channel called his popularity so great that “when visiting towns, he was given the finest hotel accommodations, free food and drink, and a guided tour of local roads. Everyone wanted him.” Like Rudolph Valentino and Babe Ruth, he even inspired imposters.

“Chief” began a radio propaganda campaign for better roads in 1923. He persuaded Congress to grant him authority to sign contracts with states. He used that to promise states money that the U.S. Government was obliged to fulfill. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) would fight in vain to have MacDonald’s powers repealed.

The Great Depression threatened to stop all road building. FDR suggested a work plan to build three east-west and seven north-south highways in straight lines across America. MacDonald persuaded him to forget the straight lines and connect every state’s big cities with the others in “an interstate highway system.”

Roosevelt needed to carry Pennsylvania to win a third term, and “Chief” was his main man on the job front. In 1938, he told McDonald to build a turnpike across that state’s mountain ranges, from Harrisburg to Pittsburgh, before the 1940 election. Blasting through mountains and ramrodding a crew of 20,000 working 24-7-365, MacDonald delivered the turnpike in less than two years. You read that right — 203 miles through rugged mountains in less than two years. That is twice as fast as it now takes to rebuild 20 blocks on Ingersoll Avenue.

World War II brought MacDonald’s next impossible mission. FDR asked him for a highway from Seattle to Alaska to protect America’s most vulnerable asset from invasion. Again, “Chief” delivered against all odds and acts of God. Japan retreated from island occupations nearby.

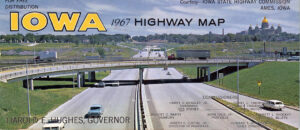

The MacVicar Freeway graced the cover of the 1967 Iowa Official Highway Map. This scene looked east from the Third Street overpass toward the Des Moines River and State Capitol. The curved entrance ramp from Second Avenue north to I-235 west was rebuilt in 2003.

MacDonald retired after Dwight (Ike) Eisenhower became the seventh U.S. President he served during his 30-plus years as roads chief. Ironically, Ike would get credit for realizing MacDonald’s vision of an interstate highway system. And two mayors named MacVicar were honored on Des Moines’ freeway. Chief went on to help Central America build the Inter-American Highway.

In 1949, historian Stephen B. Goddard wrote, “MacDonald was a force as powerful as his counterpart at the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, yet he was virtually unknown to most Americans.”

MacDonald died in Texas in 1957 and was laid to rest in Maryland. A simple tombstone was added to his modest grave in 2013.

(All these 19th century men died a long time ago. There are many conflicting reports about details of their lives. This does not intend to be a consummate history, just a good tale about men of honor. As Kipling wrote, “Lest we forget. Lest we forget.”) ♦