Casablanca

1/3/2018The 75th anniversary of America’s most beloved motion picture

The motion picture “Casablanca” opened to American audiences 75 years ago, on Jan. 23, 1943. Since its release, it has arguably become the most enduring and beloved motion picture in American cinematic history. Its run time is a mere 102 minutes, but it offers all the characteristics that draw us to movies: drama, intrigue, suspense, murder, comedy, romance, plot twists and a surprise ending.

The motion picture “Casablanca” opened to American audiences 75 years ago, on Jan. 23, 1943. Since its release, it has arguably become the most enduring and beloved motion picture in American cinematic history. Its run time is a mere 102 minutes, but it offers all the characteristics that draw us to movies: drama, intrigue, suspense, murder, comedy, romance, plot twists and a surprise ending.

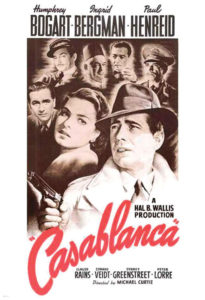

The movie was named the Best Picture at the 1944 Academy Awards. Michael Curtiz won the award for Best Director and the writing team of brothers Julius and Philip Epstein took home Best Screenwriting honors along with Howard Koch. The Warner Brothers picture was also nominated for Best Actor, Actor in a Supporting Role, Music, Editing and Cinematography. The movie was adapted from a play called, “Everybody Comes to Rick’s,” written by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison.

The movie follows Rick Blaine, an American expatriate running a popular nightclub and gambling parlor in Vichy-controlled Casablanca during World War II. The city is a key embarkation point for refugees attempting to flee the Nazis.

Humphrey Bogart as Rick Blaine and Ingrid Bergman as Ilsa Lund in “Casablanca.”

In an opening scene, a greasy black-marketer named Ugarte comes to Rick’s Café to ask Blaine to hide “letters of transit” that he has wrestled from two German couriers, who are found murdered. The coveted letters, signed by General de Gaulle, offer their bearer unquestioned aerial passage from Casablanca to Lisbon and then freedom to America. Rick’s Café fills with a host of inhabitants all seeking a way out of Casablanca, as well as the local prefect of police, a Nazi major and a wanted Czech underground resistance leader with his beautiful wife in tow. The characters become entangled as they search for the letters, dodge the Nazis and attempt to escape.

The movie has an A-list cast including Humphrey Bogart (Rick Blaine), Ingrid Bergman (Ilsa Lund, wife of Laszlo), Paul Henreid (Victor Laszlo, the Nazi resistance leader), Claude Rains (Captain Louis Renault, the chief of police in Casablanca), Conrad Veidt (Major Heinrich Strasser, the top Nazi in Vichycontrolled Morocco), Sydney Greenstreet (Signor Ferrari, owner of the Blue Parrot bar and “leader of all illegal activities in Casablanca”) and Peter Lorre

(Ugarte, the sleazy marketer who sets off the fuse and the ensuing chase for the letters of transit).

The January 1943 release of “Casablanca” was moved up to take advantage of President Roosevelt’s trip to Morocco for the Casablanca Conference, the meeting between FDR and Winston Churchill, which planned the future of the war effort and produced the famous declaration that the Allies would only accept “unconditional surrender” from Germany. The picture had been rushed to a brief December premiere in New York shortly after General Patton overtook Casablanca from Nazi control during the U.S. campaign in North Africa that was dubbed “Operation Torch.”

The film has memorable music (“It Had to Be You,” “Knock on Wood” and “As Time Goes By”) and memorable lines (“We’ll always have Paris;” “Play it Sam, play ‘As Time Goes By;’ ” “Here’s looking at you kid;” and “Round up the usual suspects,” to name just a few of the dozens which are quoted even by those who have never seen the movie.

Humphrey Bogart’s character is the center of all the action and Rick evolves from the self-centered sayer of things like, “I stick my neck out for nobody” into a hero who says, “You’ve become a patriot.” But the viewer is never quite sure how or why Rick takes the turns he does and we’re left to ponder whether he is driven by love, patriotism or the “10-thousand francs” he has wagered with Louis on whether Laszlo escapes the Nazis.

“Casablanca” opened to American audiences 75 years ago on Jan. 23, 1943.

The transformative scene in the movie is the vocal stand-off at Rick’s Café when inebriated Nazi soldiers begin singing the German patriotic anthem “The Watch on the Rhine.” Resistance leader Laszlo, who the Nazis want to kill, charges to the club band asking them to “Play La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem. The band leader glances to his boss, Rick, for guidance. With Rick’s slight nod, the band plays, the patrons drown out the Nazi chorus and “Vive la France” is proclaimed — as the locals win the battle with the Nazis. With his minor nod, Rick has quietly taken sides — at the same time the Nazis shut down his club because of the disturbance.

Adding to the movie’s intrigue is a past relationship between Ilsa and Rick. But movie censors of the day complicated that relationship for the writers, who were not allowed to display sex on the screen or a married woman engaged in an affair. The screenwriters solved this roadblock with the flashback scene between the two in Paris. Believing her husband had been killed by the Nazis, Ilsa strikes up a romance with Rick, who knows nothing of her marriage to Laszlo. It is only when the two are to flee the Nazi invasion at the train station that Ilsa disappears on Rick, leaving him a letter explaining that she cannot go with him. She doesn’t reveal that Laszlo has been found alive in a rail car on the outskirts of Paris. They only reunite when she walks into Rick’s Café — “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

Later in the film, Ilsa makes a clandestine appearance at Rick’s to ask him for the letters of transit so she and Laszlo can escape. When he turns her down, she pulls a gun on him to obtain the letters. When that fails, she falls into his arms, professing her love and pleads for him to “do the thinking for the both of us.” The writers avoid the censors by implying what happened at their late-night rendezvous only near the end of the picture, when Rick tells Ilsa, “We’ll always have Paris … we lost it until we got it back last night,” and then explains to Laszlo, “she pretended she was still in love with me … and I let her pretend.”

When the American Film Institute (AFI) first issued a list of the 100 greatest motion pictures, “Casablanca” was featured in the No. 2 slot, after “Citizen Kane” and before “The Godfather.” But unlike “Kane,” “Casablanca” is a motion picture fans watch over and over, reciting dialogue and being drawn in each time — almost as if they are not sure how the picture will end. It continues to win over new movie-goers and is often the feature at movie festivals around the world.

Dooley Wilson as Sam and Humphrey Bogart at Rick in “Casablanca,” arguably the most enduring and beloved motion picture of all time.

Rather remarkable, nearly the entire cast of “Casablanca” consisted of refugees. Of the 14 credited cast members, only three were American: Bogart, Dooley Wilson, who played Sam the piano player and the young Bulgarian refugee Annina, played by Jack Warner’s step-daughter Joy Page. Many of the other 11 came to America as a direct result of Hitler’s destruction of Europe, as did many of the 100 extras in the film.

Some of the actors endured tremendous struggles upon arriving in America, not unlike those shown in the opening credits, with the spinning globe frames punctuated with refugee scenes. Paul Henreid, the German actor born an Austria-Hungarian, was declared an enemy of the Third Reich. Carl the waiter, delightfully played by S.Z. Sakall, had fled Germany in 1939. His three sisters all died in a concentration camp. Peter Lorre, who had become famous in Germany for his role in Fritz Lang’s M, was an Austria-Hungarian Jew who fled the country ahead of the Nazi takeover.

Conrad Veidt was one of the most famous German actors of his day. Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels offered him a deal to continue acting in Germany if he would divorce his Jewish wife. Veidt, refusing to denounce his wife or her religion, fled the country ahead of pursuing the Nazis. It is ironic that he played the evil Nazi Major Strasser in the film.

Many of the extras had accomplished acting careers across Europe, which the Nazis destroyed with their invasions. Nearly all were unknown to American audiences and most would never regain the artistic status they had achieved in their home countries. After the war, several of them returned to their home countries, but their careers could never fully recover.

In this current politically opportunist climate against emigres, it seems ironic that perhaps the greatest piece of moviemaking in American history was largely created by those who immigrated here. It could be an apt lesson for those who desire to close borders, punish refugees and push away anyone different than themselves.

“Casablanca” was named the Best Picture at the 1944 Academy Awards.

For all its complexity, Casablanca can also be reduced to a simple love story between two characters, Rick and Ilsa. The actors who played those roles are considered two of the greatest in movie history.

Humphrey Bogart had gained movie prominence for playing hardened outlaws, like Duke Mantee in “The Petrified Forest” and Roy Earle in “High Sierra.” He shifted to hard-boiled good guy in “The Maltese Falcon” and then evolved to cynical romantic in “Casablanca.” Warner Brothers used the formula again, most notable in “To Have and Have Not,” one of five Bogey-Bacall pictures with Bogart again as the reluctant American drawn into fighting the Nazis, this time on the island of Martinique. The tough guy romantic Bogart persona, cast in “The Maltese Falcon” and set in stone in “Casablanca,” continued in such classics as “The Big Sleep” and “Key Largo,” up until his death in 1957. The American Film Institute lists Bogart as the greatest American actor in film history.

Moviegoers would be hard pressed to find a motion picture character with as much grace and beauty as Ilsa Lund, played wonderfully by Ingrid Bergman. The Swedish actress was also a refugee of sorts, having been handed from family member to family member after both her parents died in her youth. She was building an impressive acting career in Germany when David O. Selznick whisked her to America to star in “Intermezzo.” After “Casablanca,” she won Academy Awards for Best Actress in “Gaslight” and “Anastasia,” as well as a Best Supporting Actress statue for “Murder on the Orient Express.” She achieved the triple crown of acting by also winning a Tony Award and two Emmy Awards, the second shortly before she passed away in 1982.

After Rick’s Cafe is shut-down by the Nazis, the movie has a complex ending with budding plot twists along the way. The classic ending scene at the airport — from Rick’s speech to Ilsa, the airplane propeller starting and spinning, Strasser’s bounding ride to the airport, Rick’s showdown with the major and Louie’s decision on how to handle the whole affair — keeps one guessing until the plane ascends into the thick fog. It all plays out marvelously. For the viewer, it is the beginning of a one of cinema’s most beautiful friendships. ♦