A city of screens

11/5/2025

Capitol composite. Courtesy of Mark Heggen

The first movie I saw in a theater was “Ghostbusters II” at the Showcase Cinemas in Milan, Illinois. My parents asked if I wanted to see that or “Honey, I Shrunk the Kids.” It was 1989, and I was a mere 4 years old. “The Real Ghostbusters” cartoon was on TV, and I had an abundance of related toys, so, of course, I wanted to see “Ghostbusters II.” The original “Ghostbusters” film was also one of the few VHS tapes that we owned because it came with our VCR when it was purchased. My dad would put that on repeatedly until the VCR eventually snapped the tape while it was rewinding. (We paid to have it fixed.)

That first movie-going experience didn’t last long. We had to leave during the scene when all impaled heads showed up in the subway tunnel. According to my dad, I screamed louder than Ernie Hudson after the ghost train runs right through him. My parents didn’t take me to another movie until “The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles” was released in March of 1990. It was the first movie I saw from the trailers until the end credits finished. That was the moment that inspired me to go to the movies as often as I could. When my parents divorced, my dad had cable with HBO (cool dad syndrome), but my mom just had the local channels, which is where I spent most of my time. When a new movie came out, it was an event. Trailers would be released sometimes four months before the movies would ever hit the screen. There would be big fast-food tie-ins like when Pizza Hut had the “Casper” puppets or the 1998 Taco Bell “Godzilla” big gulp cups that drew kids my age to opening night. Lines would be out the door, and tickets could not be purchased online ahead of time. No assigned seating and absolutely no beer or wine sales.

Movies would live in the first-run multiplexes for a month and then for a few weeks at the dollar discount theaters. It would take nearly a year or more before they would made it the video stores and then maybe another six months to a year before they were on television. The real money was in the box office. If you missed it, you had to wait nearly a year to see it. We all know the vibes of the multiplexes: high-priced concessions, assigned seating and sometimes they might even have an arcade where you can dump more of your money in while you wait for the movie to start. The second-run theaters would be more minimal: $3 tickets, cheap concessions and, if you are lucky, the auditorium would be cleaned with one of those tiny push vacuums.

If you go back even 10 years prior, the pre-home video era existed and movies could live at theaters for a year or more. This was a time when the cities were littered with neighborhood theaters and downtown movie palaces.

For most of the 20th century, downtown Des Moines glittered at night with the light of movie marquees just like New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. Long before multiplexes sprawled across suburban malls, the heart of the city was where Iowans went for a spectacle. They had massive auditoriums lined with gilt plaster, neon and velvet curtains that parted for newsreels, musicals, westerns and roadshows.

To understand Des Moines’ cinema history, one must understand the two-family names that defined it: A.H. Blank and Bob Fridley.

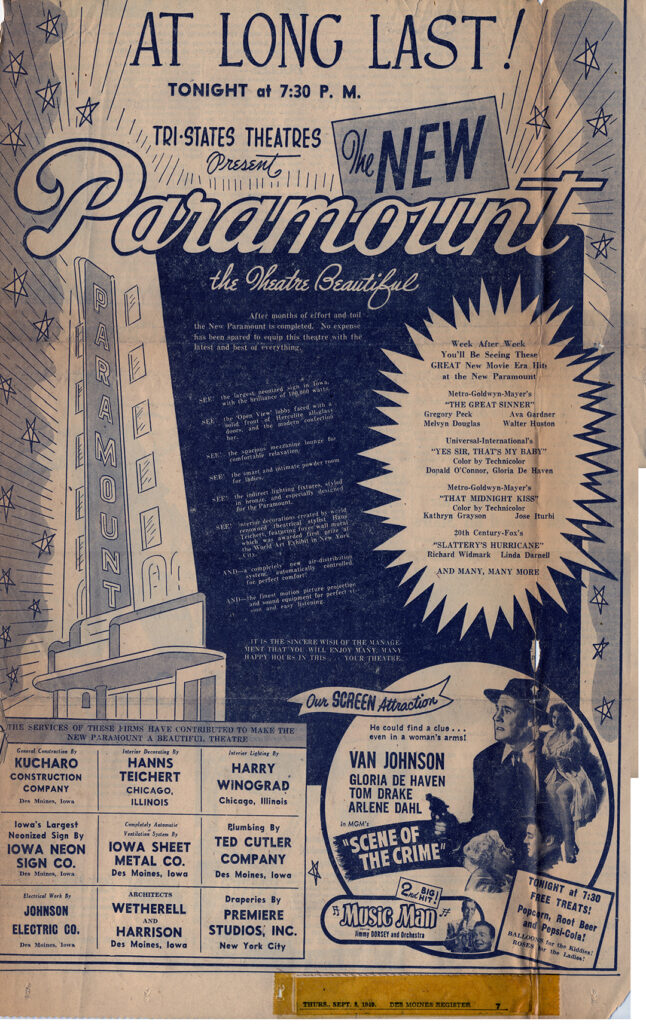

A.H. Blank was more than an exhibitor; he was a civic figure. His Central States Theatres (and later Tri-States) chain shaped Iowa’s movie culture for than half a century. Under his guidance, Des Moines was a hot spot in the Midwest’s exhibition network. Blank’s theaters were famous for impeccable presentation and community ties — employees in suits, ushers trained in etiquette, and programs that blended Hollywood spectacle with local pride.

Bob Fridley, by contrast, emerged from the small-town circuit — practical, expansion-minded, and focused on efficiency. By the 1980s, Fridley Theatres was the largest independent chain in Iowa, emphasizing comfort, modern projection, and neighborhood accessibility. The Fridleys had built some of the most beautiful movie houses Iowa had ever seen. Some theaters even had small waterfalls in their lobbies.

When television and people fleeing to the suburbs weakened the downtown trade, Blank’s successors pivoted, investing in smaller neighborhood theaters and drive-ins. The old downtown palaces, with their high overhead and aging infrastructure, could not compete. The implosion of the Paramount in October of 1979 was not just a demolition but an elegy for an entire model of showmanship.

Empress Theatre, 1920. Courtesy of Mark Heggen

The First Golden Age

(1910s-1930s)

When the Empress Theatre opened in September 1913 at Eighth Street and Locust, Des Moines joined a national wave of vaudeville palaces built to impress. The Empress was an opulent “continuous performance” house — marble foyer, red carpets, chandeliers — designed to host traveling vaudeville acts and, increasingly, the new novelty of motion pictures.

Within a few years, the city’s appetite for grander venues outgrew the modest storefront nickelodeons of the 1900s. The Empress changed names several times as national chains consolidated: Pantages, Sherman, Orpheum and, eventually, RKO Orpheum by the early 1930s. By then, the Empress was part of the mighty RKO circuit that blanketed America’s downtowns with neon and synchronized sound.

Meanwhile, Des Moines entrepreneurs were building their own empires. Among them was Abraham Harry “A.H.” Blank, a visionary exhibitor whose company, Central States Theatres, became synonymous with moviegoing in Iowa. Blank, who had started in the nickelodeon business around 1908, was a master of promotion and local investment. He saw theaters not just as entertainment venues but as civic monuments — places where the community gathered, celebrated and marveled at the modern world of the movies.

Manager Jess Day with promo coach for “The Toll Gate” at Palace Theatre, 1920. Courtesy of Mark Heggen

In 1919, Blank unveiled one of his crown jewels: the Des Moines Theatre at Fifth and Grand. Its July 10 opening marked the city’s embrace of the movie palace era. The Des Moines Theatre’s design blended Beaux-Arts elegance with a massive vertical sign that could be seen from blocks away. Inside, it seated more than 1,000 patrons beneath a domed ceiling and a proscenium festooned with gilded ornamentation. It quickly became the city’s “home office of Hollywood,” hosting world premieres such as “Happy Land” in 1943 and Rodgers and Hammerstein’s “State Fair” in August 1945. The Blank family had created a showplace worthy of the state capital’s stature.

The Paramount and the Age of Splendor

(1920s-1940s)

If the Des Moines Theatre established A.H. Blank as a showman, the Capitol Theatre, which opened Aug. 19, 1923, confirmed him as a master entertainer. Located just down the block on Fifth and Grand, the Capitol was built for spectacle. With more than 2,000 seats, an orchestra pit, a Wurlitzer organ and a marble staircase, it rivaled the finest houses in Chicago or Minneapolis.

In 1929, the Capitol was absorbed into the Publix and Paramount circuits during the great consolidation of the late silent era, and its name changed to the Paramount Theatre. Des Moines moviegoers entered under a towering marquee ablaze with incandescent bulbs spelling out “PARAMOUNT.” Inside, the theater’s decor was a mix of Moorish fantasy with Art Deco sleekness.

Box office display for “Forbidden Fruit” at Rialto Theatre, 1921. Courtesy of Mark Heggen

The 1930s were a time of glamour amid hardship. At the height of the Depression, the Paramount offered escape: Busby Berkeley musicals, screwball comedies, and Disney shorts that let audiences forget about the hard times that were happening outside. Blank’s Central States chain continued to thrive by blending local management with Hollywood supply. The Des Moines and Paramount were not merely screens; they were civic gathering points, hosts for radio broadcasts, war-bond rallies and talent contests. The movie business is often called “recession proof” because at any given time there are people looking to forget about their problems for a short moment.

Restaurateur George Formaro has an interesting artifact from this time, a printing plate from 1932 that was most likely used in The Des Moines Register.

“The 1932 plate is pure magic,” Formaro explains. “You can see ads for ‘White Zombie,’ ‘The Age of Consent’ and ‘Lady and Gent,’ which puts this right around late summer that year. These were playing at the Paramount, the Orpheum, and the Strand. The Paramount was the jewel of downtown, built for vaudeville and later converted for sound, I believe. The Orpheum, from what I’ve been able to tell, was part of RKO’s circuit, and the Strand on Locust was one of the Tri-States houses that helped shape how Des Moines went to the movies.”

Formaro pointed out that, if you look closely, you can see a small ad for a live stage show, which was still common then.

“Man, I would love for someone to walk me through what going to the movies was like then,” Formaro said. “Even if I can’t make out every detail on the plate, it feels alive. I can see my dad and uncles saving up their money and taking the trolly to see a movie. You can imagine the city at night, lights glowing, organists warming up, and people filling the sidewalks to see Bela Lugosi or George Bancroft on screen.”

Printing plate, Strand Theatre, 1932. Courtesy of George Formaro

In 1938 the U.S. Department of Justice filed suit against the major motion picture studios. The “Big Five” — Paramount Pictures, MGM, Warner Bros., RKO Pictures, and 20th Century Fox — for a pattern of anticompetitive practices including vertical integration (studios producing films and then distributing them and exhibiting them in theaters they owned), block-booking (requiring theaters to buy a block of films rather than select films individually) and clearance/first-run arrangements that favored studio-owned theaters. Many of the major studios owned or had controlling interest in chains of theaters, which created a closed system. They produced the film, distributed it, exhibited it in their theaters, and often excluded independent theaters from access. An example of this was RKO Pictures producing “King Kong.” When it came time for “King Kong” to hit the movie screens, only RKO Theatres or venues that RKO had controlling interest in got the movie. Independent theaters missed out.

This became known as the “Paramount Decrees” or The Hollywood Antitrust Case of 1948, and it changed the economics of how films got to theaters and the business models of theaters themselves. This allowed independent producers to have access to more screens, and it forced exhibitors like Central State and Fridley Theatres to concentrate more on their own amenities, design and diverse film bookings.

Fellow CITYVIEW writer Jim Duncan shared some of his theater memories.

“Paramount had a lobby for its balcony level with furniture and vending machines. They would host traveling stars there as the balcony lobby was bigger than the main floor lobby,” he said. “I met Audie Murphy there. He seemed like a high school kid, not a god. I loved the aroma of coconut oil, which was the cooking oil of popcorn then. The machines were just inside the doors at the Paramount, Orpheum, Rocket, Strand.”

By the 1940s, the Blank family’s theater network had become a regional power. Through Central States Theatres, they operated dozens of screens across Iowa, Nebraska and the Dakotas. A.H. Blank was recognized nationally for his philanthropy — funding the Blank Children’s Hospital, the Blank Park Zoo, and numerous civic projects. His theaters projected not only Hollywood glamour but a kind of Midwestern optimism.

Postwar and downtown’s decline

(1950s-1970s)

Paramount Theatre ad, 1949. Courtesy of Mark Heggen

After World War II, the shape of American leisure began to shift. Families moving to the suburbs, the rise of television and the new car culture changed how audiences consumed movies. Downtown Des Moines, once packed on Saturday nights, saw its crowds drifting toward drive-ins and neighborhood houses.

The Galaxy was a one-screen theater located on Eighth Street between Grand Avenue and Locust Street, directly across from what then was the Register and Tribune Building (now the R&T Lofts) and a short walk from the block on Grand Avenue that was shared by the Paramount and Des Moines theaters. The Galaxy location is now, unfortunately, a parking garage.

By the mid-1960s, the tide was irreversible. The Des Moines Theatre closed its doors on Jan. 27, 1966, after nearly half a century as the city’s cinematic cathedral. Its demolition soon followed, erasing one of downtown’s architectural gems. The Paramount struggled on, experimenting with reinvention. In April 1974, it reopened as Theatre Fabulous, a short-lived dinner theater experiment. By July, it was rebranded again as The Country Club, hosting live music instead of films. None of it could stop the inevitable. On Oct. 14, 1979, the Paramount was spectacularly imploded before a crowd of thousands. The blast marked the symbolic end of downtown Des Moines as a moviegoing district.

The River Hills and the end of an era

(1968-2000)

Even as the old palaces faded, one last monument rose on the south edge of downtown — a modern temple to widescreen spectacle. The River Hills and its twin, The Riviera, opened in April 1968 on Crocker Street at Second Avenue, on the plot of land where the Wells Fargo Arena eventually rose. Second and Walnut is where the Des Moines Civic Center is now. The Riviera premiered a week earlier; the River Hills followed with the Cinerama documentary “Mediterranean Holiday,” then the 70mm juggernaut “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

For downtown Des Moines, the River Hills/Riviera complex represented both continuity and transition — a bridge between the movie palaces of the past and the multiplexes of the future. Through the 1970s and 1980s, it hosted blockbusters like “Jaws” and “Star Wars” while smaller downtown screens shuttered one by one.

RKO Orpheum Theatre, 1949. Courtesy of Mark Heggen

By the late 1990s, even this last downtown fortress was losing ground to megaplexes like Fridley’s Fleur Cinema and the new Carmike complexes near the interstate. The River Hills closed on Sept. 7, 2000, ending an unbroken 87-year streak of downtown first-run movie exhibition. The building was demolished in 2003, leaving behind only photos and the faint memory of its curved screen.

While most of the theaters in Des Moines are now owned by major chains like Cinemark and B&B, Fridley Theaters is still going strong. I don’t mind driving out to Waukee to visit the Palms to check out a movie in IMAX. In the post-COVID era, I was happy to see they purchased the Fleur Cinema and kept it as an art house theater. Do I wish we had at least one downtown cinema? Sure. Something like Chicago’s Music Box Theatre would be amazing on Court Avenue, East Village or even in the upcoming Market District. The Varsity Cinema has been my home theater since it opened due to both its location and diverse programming. They have been building a great culture for film-lovers who have an affection for movies that goes beyond franchises and cinematic universes.

My last note on this subject: I want to recommend checking out director Mark Heggen’s documentary, “Lost Cinemas of Greater Des Moines.” This story could not have been written without his guidance and the research he spent years gathering. ♦