Art Cullen’s new book tells us the rent is due for Iowa

11/5/2025

Art Cullen. Photo courtesy of Ice Cube Press

With a rare sense of place, a know-it-when-you-see-it Iowa-ness, Art Cullen’s roaring new book is nothing short of an unsparing mirror for 3.3 million of us in the state. With still-night whispers of truth and bar-fight ferocity, this western Iowa newspaperman reveals the masquerade-ball leadership that’s turned so many of Iowa’s once-warm communities into furnaces of justified grievance and misdirected outrage.

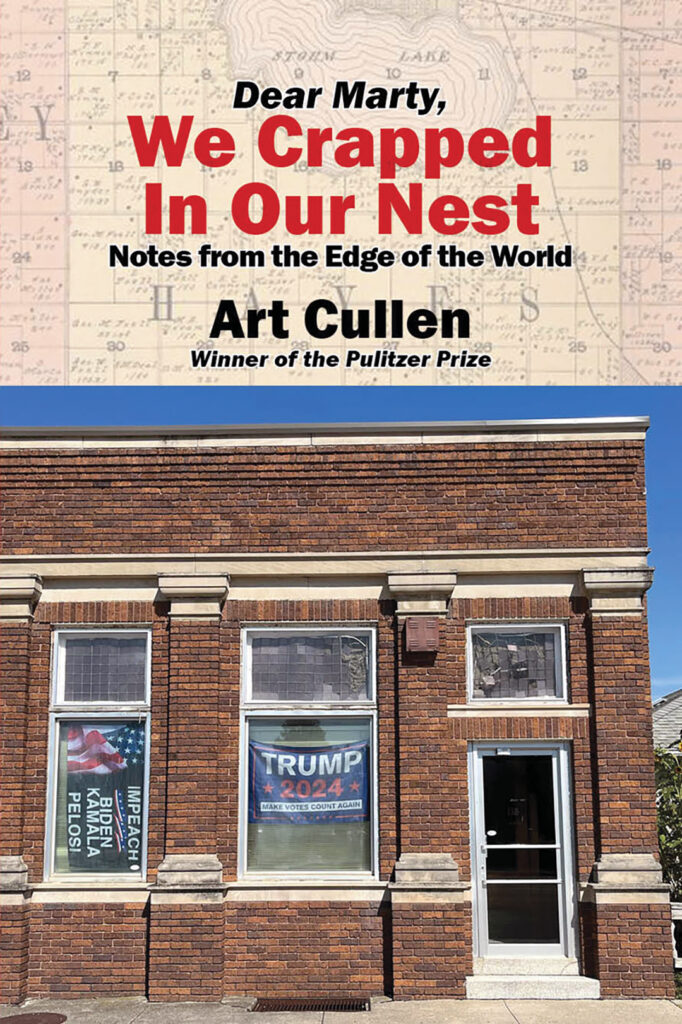

Readers will absorb the very landscape of this state with more informed eyes after completing Cullen’s “Dear Marty, We Crapped In Our Nest: Notes From The Edge Of The World.”

The roam of corn fields and barns and grain elevators around rural Iowa presents a post-card serenity to those who don’t know the hidden churns of agriculture, the millions of miles of tiling under the land rushing chemical destruction to our rivers or the exploitation of slaughterhouse workers, immigrant strivers who capture Cullen’s heart as he writes with alarm-clock urgency about their lives in his hometown of Storm Lake, Iowa, The City Beautiful, which is all the more so, Cullen writes soaringly, because it is one of the more diverse communities in Iowa.

“We get along pretty well,” Cullen says of Storm Lake. “We have to. Most of rural Iowa loses population every year. Storm Lake grows while speaking 30 languages.”

The book, published by the independent-minded Iowa-based Ice Cube Press, is a collection of timely and timeless meditations, structured by Cullen as a series of letters to a former high school classmate, on Iowa’s people, land and politics — but mostly the land, because as Cullen explains, that’s where it all starts and ends in Iowa.

“The Dust Bowl ended in 1939 only with the cyclical return of rainfall to end a 20-year drought,” Cullen writes. “Surprisingly few lessons were learned from this disaster.”

Art Cullen is to Iowa what William Allen White was to Kansas a century ago. The late Kansas publisher, the “Sage of Emporia,” White — a Pulitzer-Prize winner like Cullen — earned a national following with insightful and poignant writing from a rural newspaper office. White started more conventionally than Cullen but found the same progressive lane Cullen so fully inhabits.

Iowa-based Ice Cube Press published Storm Lake journalist Art Cullen’s new book. Photo courtesy of Ice Cube Press

Through a seven-decades-deep understanding of small towns, an intimate and intuitive sense of his fellow rural Iowans, Cullen comes to understand what other journalists miss. He describes where Iowa is now with breathtaking clarity.

“When you lose the sanctuary of shared experience, shared prosperity and shared desire to see your stake in community grow, being put in your place incites a simmering rage,” Cullen writes. “There is a sense of loss of comity, of kinship in ownership, where your differences become your only mutuality, and you wonder what you are doing here. You are trying to build a house where nobody is left with the key to the door.”

I know this book to be true because I know Art Cullen to be true. I’m a fourth-generation Iowa newspaper publisher who lives in Carroll, an hour south down Highway 71 from Art Cullen’s Storm Lake. We may have smoked different brands of cigarettes (Marlboro Red for Cullen, American Spirits for me), but we operated the same printing presses, literally and exactly.

“Dear Marty” is, at times, heartbreaking. I know the Iowa Cullen longs for, because I lived in that time and place, too — albeit a generation later, but nevertheless in a place where kindness and credentials mattered.

“If you cannot imagine a town of 68 people, you might not be able to appreciate how things get done around here,” Cullen writes.

We used to have a church-potluck civility in rural Iowa, not communities — families themselves even — cleaved by political differences.

Not too long ago, people in our small towns “recognized their differences were artifices created in their minds by someone who never turned a wrench or was chased away by a farm dog through mud,” Cullen writes.

The Storm Lake Times Pilot, Art Cullen’s family newspaper, still understands this, and it shows in the news coverage. This was particularly true during the COVID-19 pandemic when the newspaper reported to its readers — and the state and the nation with the reach of Cullen’s voice — the deadly disparity in how Gov. Kim Reynolds and others managed risk. The federal government bailed out farmers but forced packinghouse workers to stay in their jobs, and often die for it.

“The farmers are white,” Cullen writes. “The people dying, overwhelmingly, are not.”

Villains and heroes aplenty populate “Dear Marty” with the former generally being people you’ve heard of before. The consolidators of agriculture come in for special fury.

The heroes in the book often are people you don’t know, the everyman, small-town guys who make us what we are, from the musician-businessman in Auburn (who I know, too) to the immigrant down the street from Art Cullen in Storm Lake (who I know, too).

“Dear Marty” will get you to think. But that’s just it; it requires you to think. Cullen might be able to break through to more people than most journalists because his writing is tied to an abiding curiosity that’s essential to uphold what all good small-town editors must know to get the paper out: Everyone has a story. Art Cullen’s demands to be read.

“As the mural warns on the abandoned motel on a highway in the Navajo Nation off the beaten path of interstate freeways packed with campers and 18-wheelers” ‘The American rent is due.’ ” Cullen writes. “There’s no avoiding it.”

Cullen knows how much that rent is. He might be the only one in Iowa who does.

NOTE: Art Cullen is scheduled to speak at the Harkin Institute in Des Moines on Wednesday, Nov. 12 at 6 p.m. ♦

Douglas Burns of Carroll is fourth-generation journalist and founder of Mercury Boost, a marketing and public relations company.