The Shuler Mines

10/6/2021Waukee was once a “company town.”

The Shuler family. Image provided by Darlene Oliver from her self-published book “The Shuler Coal Mine.”

I have been spending time lately in Bentonville, Arkansas (seven days a month since July to be exact). Many scholars of useless information will tell you about Bentonville being the mecca of the retail universe. I’ll save you the time of Googling and tell you it was the birthplace of Walmart.

Bentonville is a company town. There are no grocery stores other than Walmarts. A museum in the town square was the original Walton 5-10 where you can order $2 ice cream cones in a variety of flavors, all inspired by Walmart. There is even a high-end social place called The Walton Club. “Stepford” immediately comes to mind. This, my dear friends, is a company town.

Iowa has had its share of company towns, too, some that prospered and others that relied too heavily on a large single employer that was “too big to fail.” Webster City, Forest City and Newton may come to mind. Maybe surprisingly, Waukee was also once a company town. The Shuler Mines once roared life into this small town. They were run by the The Shuler Mine Company based out of Des Moines. The company had mines in Lovilia, Iowa; Alpha, Illinois; and Steamboat Springs, Colorado. The Waukee mines opened in late 1920 and would grow to be the largest coal producer in Iowa with the deepest mine shaft — 387 feet into the earth.

A Miner and his Young Son. Image provided by Darlene Oliver from her self-published book “The Shuler Coal Mine.”

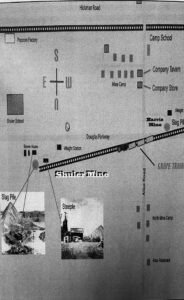

The Shuler Mines were such a huge employer that they built camps for their employees that included strips of homes with a public school, a tavern and a general store. Bruno Andreini was a child when his father was working in the mines. Bruno is now 81 and one of the few “children of the mines” remaining.

“My dad worked in the mines from the very first day in 1921 until it finally closed in 1948,” Bruno said. “It was a very simple life. We were poor but also rich in a lot of ways.”

Bruno was not allowed to explore the mines with his father, as his mother thought it was too dangerous. Looking back, he wishes he would have. I found a publication on The Shuler Coal Mines from the Waukee Public Library that mentions, “The miner’s wife had their share of worrying about her husband’s health. She was concerned about her husband just returning home at night.” I guess the last thing the Andreini mother needed was worrying about her child coming home, too.

The camps had a nickname: “Stringtown.” At their peak, they functioned like a village of their own next to Waukee proper.

Map of the Shuler Mining Camp. Image provided by Darlene Oliver from her self-published book “The Shuler Coal Mine.”

“We even had the Shuler Coal Baseball team with some pretty good players,” Bruno said. “We really socialized like a town.”

Bruno remembers having a hand-cranked magneto telephone and a line shared by 13 other families. If they weren’t careful, anyone from those families could pick up the phone and listen in on the conversation. None of the of homes in “Stringtown” had a working shower, but instead had tubs that were 3 feet in diameter. Many of the residents would walk a half-mile from their homes to the mines where there were facilities to take a real shower.

The Shuler Coal Mines didn’t end in an abrupt manner like some did. You may have seen the movie “Nomadland” or read the book of the same name. When the gypsum mine closed in Empire, Nevada, the town was abandoned and lost its zip code. All mines, by design, will eventually close.

“By the time the mines closed in 1949, many guys like my dad had made it to retirement age,” Bruno remembers. “The town really didn’t suffer much. Some people moved away to mine in other towns, but others were ready to be done. That’s good planning.”

The homes of Stringtown are now gone, and all that is left is a name on a sign called “Stringtown RD.”

The Waukee Public Library has a small museum dedicated to the Shuler Mines, and an elementary school carries the same name. Bruno and a few others of his age continue to share these firsthand stories.

There is a lot to be said about folks who faced hardships due to their career moves. Not everyone had choices in those days. Bruno says he was fortunate that he didn’t lose his own father to the mines like so many did.

“Life was really hard,” Bruno said, “and not that I always want to admit it, but it made us who we are today.” ♦

Kristian Day is a filmmaker, musician and writer based in Des Moines. He hosts the syndicated Iowa Basement Tapes radio program on 98.9FM KFMG.

Interesting article. Charles Shuler, owner of the mine, was my great-great uncle. He lived in Davenport and his home, called “Hillside,” still stands and is on the National Register of Historic Places. His sister Sophia was my great grandmother. Sophia married John Ramsay of Oskaloosa who also owned mines. They had seven children. Their youngest daughter was my grandmother.

I also am a child of the mines..Dominic Ma tunfredini. My father , Frank Manfredini worked in the Schuler Mines for many years.